Many of my clients of lately have been working with naming conventions for all kinds of things. Some examples are Service Principals, Projects, AAD Groups, Azure resource groups, etc etc.

It seems that naming conventions have become an accepted -or even recommended- approach within many organizations. For some reason small groups of administrators enforce rules that might benefit them, but are holding thousands of other users back. And while I see a little merit in naming conventions from their point of view, I doubt that it is worth the trade-off. In this post I want to share some of the drawbacks of using naming conventions I have encountered.

Maybe we should reconsider doing this naming conventions thing?

Names become impossible to remember, work with or pronounce

A given Azure application can quickly span a number of components. An average resource group I work with has probably anywhere between ten and twenty resources in it. If three of these resources were databases, it is great if the team can refer to them using meaningful names. That is really hard if they are being called 3820-db-39820, 3820-db-399454 and 3820-db-730244. It makes any meaningful conversation impossible. Just imagine you are being called about the 39820 database, how do you even know what that is and what it does?

Having a customers database, a users database and an events database, it would be great to just name them customers, users and events. it makes any conversation about them much easier, removes noise, looking things up in source code or configuration and the work of the development team becomes much more fun. Imagine joining a team that runs five components with on average five teen resources, not pleasant at all.

I know it is a bloody database

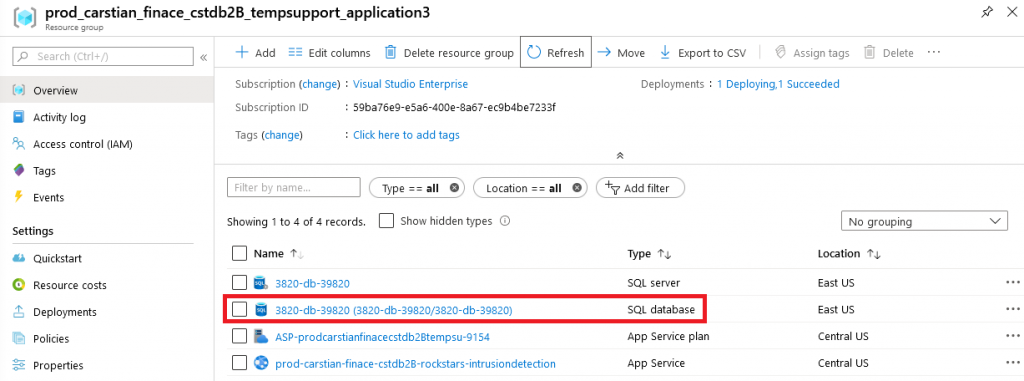

And while we are on the topic of names like 3820-db-39820, everyone already knows it is a database. The team that created the database only deals with databases, so dûh! And the team itself can see it right next to the name:

User interfaces cannot deal with your overly long names

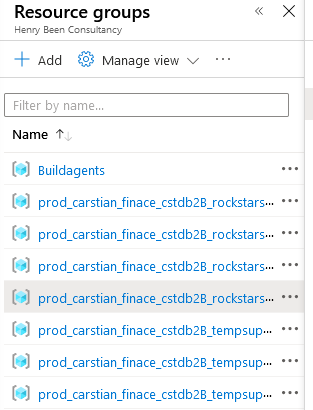

Another customer of mine had a naming convention for Azure resource groups. In my opinion quite ridiculous since every resource group is already in a subscription and those can in turn be organized into management groups. A great way for mimicking your organizational structure and seeing what a given resource group is about. So no need for calling them {businessunit}_{department}_{project}_{team}_{freetext} really. But of course some admins still do, delivering the following interface:

Trust me, no fun when you have to work with your resources the whole day. And this happens with many types of naming conventions. Here is another example, now using AAD groups that follow naming conventions.

With many naming conventions, many examples can be found in many different tools. Tools are simply not designed for displaying long, weird names that are supposed to encode all kinds of information. If you add in a bit more of duplication of information like resource type and resource location it becomes even worse.

How do you cope with changes?

Let’s assume two departments in your organization get merged. You now have two options:

- Do you rename hundreds of resources?

- Or do you leave hundreds of resources with deceiving names?

Your pick!

A hint: in many tools and systems you cannot change the name of a resource after creation.

Behavior gets attached

Now let’s switch from things that are just annoying to things that can be potentially dangerous. Just for fun, ever tried calling your new App Service not appsrv_{meaningfullname} but db_{meaningfullname}? I bet there will be one or two administrative scripts breaking soon after.

Another problem I just recently encountered is that of conflicting conventions. At one customer all Azure resource groups were prefixed with a certain identifier for the team name, let’s stay team-{number}. For example, team-0125 and team-5578. This had been going on for a while and more and more dependencies were taken on that convention. One team for example allowed for requesting new pre-configured databases and then automatically added that to the correct resource group based on the team number. A second team scanned all resources and calculated internal cost allocations based on the name of the resource group, etc etc. A few months after establishing the convention and adding all this behavior on top of it, a new off the shelve application was purchased. The team that bought this application had only one request though, and that is if some of the resource groups it should target could start with module-.

Uh-oh!

Implicit assumptions all around

One thing I have learned to not underestimate is the amount of reverse-engineering going on within organizations. If I name my resourcegroups {projectnumber}-{somethingusefull}, and I don’t tell that the first part is a project number, or folks don’t listen, all kinds of assumptions can start to arise. Imagine that there are also cost centers that most of the time have the same number as the project that they belong to.

Mixing in some attached behavior and confusion will quickly lead to errors. The things that can go wrong when automation teams start their work on the assumption that the first part of any resource group name is the cost center…

There are better approaches

The real problem, in my opinion, is that the names of resources, groups or things are not meant for encoding all sorts of information. And in reality, you don’t have to either.

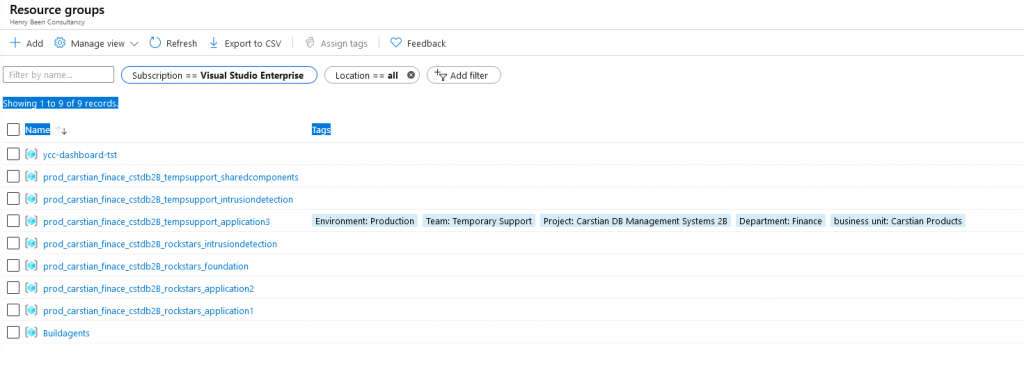

More and more systems now provide the means for storing extra information with a resource. For example Azure supports adding tags to your resources. It is as simple as adding key/value pairs with descriptive, well-formatted, not abbreviated names. With recent changes to the Azure Portal, you can now even have them render in your lists. As an added benefit, tags are also easy to remove, add, rename and correct. Giving administrators all the information they need, without needing to burden users with long names:

Active Directory for example supports extension attributes. And of course, if tags are not supported demand that they be added to the system you are using. Try to push for the correct solution, instead of trying to work around the issue.

As a conclusion, I have learned that naming conventions have downsides even though they seem to be an accepted practice within many companies. While they may bring value, I really hope this can serve as a reminder for myself and a warning for others when they think it is smart to introduce. Let’s try to not be that person that forces hundreds or thousands of colleagues into some structure that really hinders them, only for our own convenience.

And if we really have to use naming conventions, can we please have the least significant part of an naming convention first? {team}-{department}-{businessUnit} will at least solve most of the everyday problems of the impacted users.